Santa Cecilia

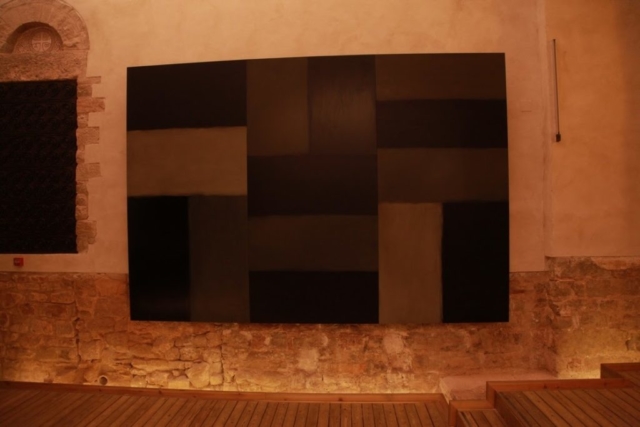

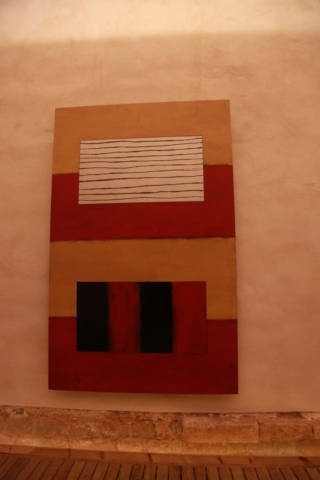

In the heights of Montserrat, near Barcelona, Sean Scully's masterpiece of sacred art opened its doors in June 2015.

The fruit and the sign of a friendship

The first time I read about Santa Cecilia, it was on a paper tablecloth in a restaurant in Chelsea, in November of 2010. This was the first time I was having lunch with Sean Scully. In this rather quiet Chelsea restaurant, our conversation rolled around his mission as an artist and mine as a priest. At some stage in the conversation, Sean Scully told me he had something important to share. His eyes were bright and his face beaming like that of a child. Digging into his side pocket, he found a pen and started drawing on the paper tablecloth: the line of a wall, the curve of an apse, loosely outlined crosses, and what stood for a large, rectangular canvas made of two rows of seven panels, the upper row, he explained, painted in heavenly tones, and the lower one in earthly tones. And before a “couscous royal” was to claim his undivided attention, he lovingly wrote a name on the paper: Santa Cecilia.

Since that day, which I remember each time I look up at the framed fragment of paper tablecloth in my Brooklyn home, Santa Cecilia kept unfolding in our conversations. I knew something beautiful would come out of such enthusiasm and dedication. But what I did not realize right away was the importance and magnitude of the project, arguably the most important collaboration between the Catholic Church and a contemporary artist since Henri Matisse spent the bulk of his last decade designing a chapel for a Dominican convent in Southern France.

Celebrating my first mass at the « Matisse Chapel », in Vence, is an experience that has left a profound mark on my priesthood. I have often been asked what difference it makes to say mass in Matisse’s masterpiece. While the Eucharistic miracle is neither augmented by the beauty nor diminished by the mediocrity of the surrounding walls, there is no question that the sense of gratitude, reverence and wonder with which Matisse has imbued every detail of the chapel he lovingly called « la Sainte Chapelle de son cœur » is a worthy case for the “sacrament of love” and that it prepares the soul to its reception. In that sense, it has been more formative of my Eucharistic experience that many books and classes.

Matisse’s Our Lady of the Rosary and Sean Scully’s Santa Cecilia are not just next to each other on the timeline of sacred art history. They belong on the same genealogy. Their spiritual kinship stems from a common origin: both are the consequence on an encounter, the fruit of a friendship. Matisse was drawn into the adventure of sacred art by Sister Jacques Marie, a Dominican nun whose genuine love and joyful faith inspired the master, opening before him new and inviting mysteries. He wholeheartedly undertook the journey, not only as an artist, but primarily as a man who had « devoted his life to the search of truth. » Matisse’s true greatness shines nowhere as bright as in the childlike awe with which, at the peak of his art, he humbly peered into these newly discovered heights.

In that regard, Matisse’s correspondence with Father Marie Alain-Couturier o.p., — the priest credited for renewing the dialogue between the Church and the arts in post-World War II France — is of particular relevance. These letters express a respect and an admiration that are sincere and mutual. They reveal Matisse humbly inquiring about the tradition, asking the theologian about prayer, liturgy and the Gospel narratives, striving, great as he was, to understand and to serve a reality which, he intuited, was greater than his art. As Father Regamey o.p., wrote it, reflecting on Father Couturier’s mission: “Friendship between priests and creators, free of agendas and preconceptions. […] For their work to be substantially nourished by them, artists should discover and deepen the realities of Faith, not through a written document, but alive and incarnate in their friend.” [1]

I heard the name of Father Laplana years before I would actually have the joy to meet him in person for the first time. From the outset, I understood that there was, for Sean, something unique and new about this encounter. Sean Scully is an independent, free spirit. His nature leans towards irreverence and rebellion. However, he would always talk about Father Laplana with affection and, I cannot find a better expression, a kind of filial devotion. When he showed me the pictures of “Pa-dre La-pla-na” (as he would always call him, muting for the occasion his Irish-American accent to the best of his capacities) pouring water on the forehead of his son Oisin in a chapel of Montserrat, when he told me about the long hours spent walking in his company, the monk gently holding his arm while conversing on art and life, I understood that he was a lot more for him than just a collaborator on his largest installation to date, and that Sean had found in the heights of Montserrat more than just a prestigious and challenging commission. He had found a spiritual home, for him and for his family, as an artist and as a man. And exhibiting a picture of his baby son still dripping wet from the baptismal water, he added with fatherly pride: “You understand, when you look at him, it would be illogical not to believe in God.”

Like the “Matisse Chapel”, Santa Cecilia is the fruit of an artist’s long spiritual journey, a fruit made possible by an encounter, a friendship with a living witness of the Gospel. May it also be, for our generation and generations to come, a sign of the friendship between art and faith, a long neglected friendship, much to the loss of both parties. For, as John Paul II put it, “the synthesis between culture and faith is not only a requirement of culture, but also of faith . . . . Faith that does not become culture is not fully accepted, nor entirely reflected upon, or faithfully experienced.” [2]

F.P.

[1] Father Regamey o.p., Art Sacré au XXème siècle?, Editions du Cerf, Paris, 1952

[2] John Paul II, Speech to the participants of the national congress of the Movimento Ecclesiale di Impegno Culturale, 16 January 1982