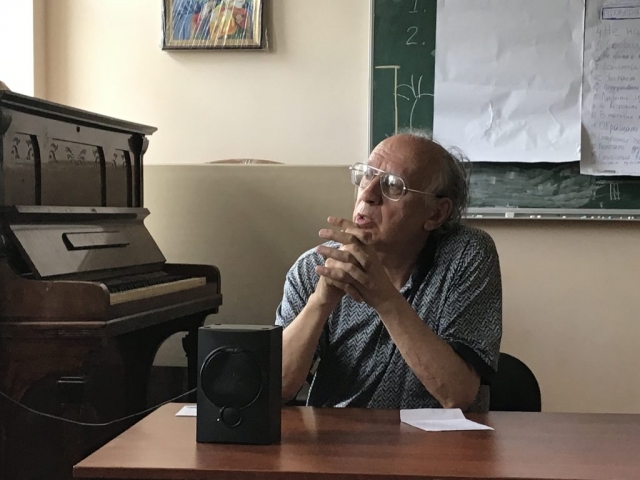

Valentin Sylvestrov

The music of vulnerability

From July 2-11, the St Clement Institute hosted a series of meetings in Lichnya, Ukraine, centered on the theme “Liberty, Authority and Service.” Among the many encounters there, the composer Valentin Sylvestrov shared some of his work and commented on it. In this exclusive interview for the Catena Artistorum, he highlights his musical search for the meaning of the human person and offers his perspective on the war in the Ukraine.

What was the beginning of your musical journey?

Well, it so happens that life has made a musical experiment of me. Due to the Soviet environment, I was able to take advantage of the birds, unafraid and free. In our social environment, we had no idea what contemporary music was, but movies popularized classical music. So that’s where I started. Then I discovered contemporary, dodecaphonic (twelve-tone), and experimental music. Today, I’m finding myself back at the beginning, at the starting point.

There’s a phrase of T.S. Eliot’s that Guillaume de Machaut always quoted, the origin of which no doubt goes pretty far back: “In my beginning is my end”. He is talking about a return to the starting point. To be back at the starting point implies a certain naivety, but also an experience of being disarmed. Yet with most composers, this attitude is the mark of a style which comes late to them, that we can see for instance with Beethoven.

This realization gave me the possibility of beginning to look at liturgical music. Just as the iconographer has to fast before writing an icon, a composer needs to be set free from pride in his or her technical expertise – it’s a form of fasting, a “kenosis”(1) for the composer.

I understood this one day when I wrote a brief prayer: My God, give me the grace to compose music which has no trace of its composer. I felt myself guided by those words. I have tried to follow them without being hindered by my technical expertise as a composer. It’s a way of approaching music similar to Gregorian chant.

So, through a kind of simplification, you have sought the possibility of new inspiration?

To make this idea of kenosis more concrete, I chose a pretty rare genre called Bagatelle. It’s a genre that is missing the pretentious need to say something grandiose. So this has opened up many possibilities to say something else. It means there’s a rare opportunity for composers.

But it’s not so much this biographical dimension as it is about a witness to the ancient connection between word and music. We could say these “Bagatelles” are little things, that don’t amount to much. It’s sort of the unleavened bread of music.

This way of approaching words allows us to approach the grandest texts without being too intimidated by the aura surrounding their author. The most important words in human history were pronounced by human lips. When we add music to that, we feel almost like imposters. We could say, in a manner of speaking, that if a composer does not serve a word, he or she disfigures it.

So must the author disappear?

The idea of this kenosis is not that the author is totally effaced. There are two types of personalism. One exalts the person – like the heroic personalism of Nicolas Berdiaiev – and the other is much humbler, which is the one that interests me.

The first moment liberates us from this sort of dependence on attributing something to an author. Bagatelles music seeks to capture that musical moment through a keen attentiveness. Because the defining characteristic of musical moments is that they have no limits. They open up something which begins but has no end. Our instinct is invited to follow, to continue this movement. This is why there are certain words, like “interesting” which are simply not applicable for commenting on music. Yet that’s what I hear a lot. In saying something is “interesting”, it creates a distance because it’s a mundane, banal word that is never able to say “I love”. Yet music has different purposes and its’ first mission is consolation, like the Holy Spirit.

You mentioned attentiveness – does this speak to a hunger to return to reality?

I don’t know. Hard to say. For sure it means that instead of struggling to find pearls we need rather to listen and wait. We could say that it’s another way to open a door into reality.

In traditional, classical music there is a certain anonymity – is this what you’re looking for?

No, I think about it differently, because there is something we can learn from traditional music. There is the idea of something which we should copy. Yet since Bach composed music, we cannot put the human person aside.

Why personalism? Classical music developed as writing, so, as opposed to Gregorian music, in classical there is an incredible amount of precision in the notation. They say that we made a mistake with music in somehow trying to capture so many precise details. They say that we did something wrong in somehow trying to capture so many precise details. But if we try to write down, to “pin down”, each piece of music, it’s not because we think we cannot play it unless we have such precise detail. It’s rather to keep in mind something precious, which might disappear without such precision. Perhaps it might seem naive to try and “pin down” such movement, but this is what allows us to remember what differentiates the great masters like Bach and Beethoven. It’s what allows for nuance in those differences, rather than looking at them in a superficial way like the mountains that never look at each other. These movements are the marks of certain persons, and this idea of the person is inherently and uniquely Christian.

Jacob Druskin, a Soviet era thinker, said that the Old Testament was epic and the NT was lyrical. In effect, the Old Testament is concerned with a people and the New is concerned with the individual person. Obviously this is a metaphor, but it shows that personalism flows directly from the Kergyma (2) in which there is no such thing as anonymity. Also because of this, we can understand the profoundly unjust and terrible nature of war, because it renders anonymity commonplace. Since the person is created in the image and likeness of God, every time we kill a human being, whether justly or unjustly, we destroy the face of God. We cannot make clear enough the cosmic nature of this drama.

How does music overcome this lack of personalism? Does it offer a response?

I would like it to, but it’s pretty insufficient. We must confirm with our actions the things said through word and music. Emile Cioran, known to be an atheist, said quite unexpectedly one day: “God can thank Bach, because Bach is the proof that God exists.” Without being a theologian or spiritual writer, he says something which is perhaps connected to your idea of compassion and an attentiveness what is proper to being a human person. Music fills this role.

On that note, it would be a good idea to unite the representatives of every Christian denomination to affirm the commandment “Thou Shall Not Kill”. This commandment is dramatically relevant, and we cannot work with sublime forms or seek out new depths of beauty without at the same time, in one way or another, finding a way to not concede anything to the slaughter. This is not only a humanistic ideal, but also a profound idea, which affirms that since God can only become present through a human being, without a human person, God is, in a sense homeless.

The author Saint-Exupery wrote to a friend that “We should give human beings a meaning, a spiritual restlessness; we should rain down upon them something which resembles a Gregorian chant…because human beings no longer understand anything except the robot and they become robots.”

This idea of Saint-Exupery is profoundly true because of a particular aspect in Gregorian chant – in such a music, it makes you think of a candle, of a fragile flame which responds to every draught of air. This movement manifests something something deeply human. Because the human person is not a rock. We think that the human person is solid and unchangeable, but humanity is perfectly represented by this “sung vulnerability”. This false impression of invulnerability is not only an illusion about the human person, because life itself is sometimes hidden behind a facade of solidity. Yet this music opens a window in these facades.

Also there is the fact that this vulnerability is not only a characteristic specific to Peter or Paul. Because once you have experienced this for yourself, you know that everyone is vulnerable. You can no longer shoot anyone, telling yourself that “it’s only a rock”, because you know that everything is vulnerable and you experience a solidarity in this vulnerability.

Isn’t this the beginning of compassion?

This is the beginning of compassion, but it’s also the beginning of the image and likeness of the Father. If it isn’t brought into this intimate connection with God, everything is lost.

In addition to what Saint – Exupery mentioned, there is no doubt also an urgent need to be able to once again capable of hearing voices and seeing persons…

This is a truth which can be understood, especially in terms of the current conflict between Russia and the Ukraine, like this: among the thousands of dead, each person killed is worth as much as the president of this or that country. We continue to fight and aggression replaces the effort to put into place the capacity of human beings to enter into dialogue. This is an obvious lie counter to the nature of the human person and counter to the existence of concrete people. Do you see fascists or juntas in the Ukraine? It’s really a lie. Already in the Soviet era we often cited this phrase of Lenin’s that the Western democracies were stupid or they were too easy to fool. Their naivete led them into two wars. Democracies are obsessed with procedures. But when there is an earthquake, there is an immediate reaction. More rapidly in case than this political or military disaster. We didn’t respond quickly enough, and this resulted in too many victims.

Let’s take the example of Boeing MH17. Many foreigners were killed. It’s obvious that it was shot down by Putin’s weapons, even if they tried to blame the Ukrainians. In the Ukraine, we have access to different points of view in the official newspapers. In fact, we heard the Russian television version which claimed that the Ukrainians were mistaken in their target and wanted to bring down the Russian president. The immediate use of this version, without any nuance, shows clearly that it was prepared beforehand.

Forgive me, but sometimes I wonder. We examine these sublime realities instead of looking for solutions to protect our lives. We often make the essential an abstraction. I’m not dead, I haven’t suffered what many have suffered, and so I don’t forget easily when someone has been killed. We have to say it and react immediately. The word “victim” is the wrong word, because it makes the thing acceptable. We are talking about murders and assassinations. We have to react immediately.

Yet at the same time, when reality becomes absurd and violent, isn’t it also urgently important, even if it seems paradoxically futile, to listen to these “Batagelles”?

When you see the memorial of the 100 heroes that were killed at Maidan, you almost feel ashamed to be alive. We cry out: “heroes never die”, yet we prefered silence to this cry which is wrong.

Hitler was listening to Bruckner in 1943 while the world was collapsing. Evil is a virus – we give it nice names, but it’s a toxic virus (3). Demons are viruses. When we pray “Lead us not into temptation”, we are asking: protect us from viruses. Music cannot heal everything. But I believe that each of us can try to do what we can where we are.

This is in connect to the personalism that you evoked. We could say that music can only heal if there is a person there to truly hear it…. This implies an encounter.

It’s true, personalism is possible where relationships exist. But when I write something, I don’t write it with the intention of making an encounter possible, I don’t even write it to explain personalism. I think this is what comes afterwards. This is not anonymity or technical expertise, it really is something personal, but the tomato isn’t thinking that it will be eaten…

Excerpts from an interview by Constantin Sigov, in Lynchya, Ukraine on July 3rd, 2017. Edited by D.C. and translated from Russian.

(1) “Kenosis” is a theological term used to describe the complete radical self-emptying love of God made manifest in the incarnation of Jesus Christ. “Jesus Christ did not deem equality with God something to be grasped at, rather, he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave.” Philippians 2

(2) proclamation of the Christian Gospel

(3) at the moment when the composer was speaking, the Ukraine was under an enormous viral attack